May 2014 - One Homesteader’s Impact on Dakota Territory

A dream and 160 acres were not enough for some homesteaders to live on in Dakota Territory.

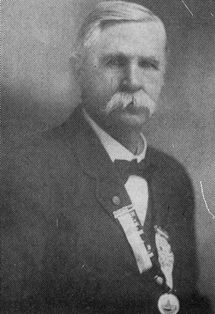

But some homesteaders weathered drought, blizzards, grasshoppers and low crop prices to stay and leave their mark on Dakota Territory and then South Dakota. One such person was Benjamin B. Potter, better known as B.B. Potter.

Potter was about 39 years old when he arrived in Walworth County, one of the thousands who poured into Dakota Territory during the Dakota Boom of 1878 to 1887. Potter was born in Pennsylvania in 1845 and, as a child, moved to Illinois and later to Iowa. After serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, he returned to Iowa and taught, farmed and was a pharmacist.

Under the Homestead Act of 1862, any head of household or adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government could claim 160 acres of surveyed government land by living on it for five years and paying a filing fee. Claimants were required to “improve” the plot by living on the land, building a dwelling, making improvements and cultivating the land. Title could also be acquired after only a six-month residency, provided the claimant paid the government $1.25 an acre. A special aspect of the Homestead Act was that Union veterans of the Civil War could count their service time toward fulfillment of the five-year residency requirement.

In a letter to a friend that appeared in the jubilee edition of The Selby Record on June 19, 1975, Potter described his experiences as a homesteader. His experiences were common to other settlers.

In the summer of 1885, Potter walked over much of Walworth County when he helped assess it. He served as a delegate to the constitutional convention in Sioux Falls that fall. Potter and his bride, Lulu, filed on adjacent quarters about eight miles south of Selby, near Bangor. Before returning to Iowa for the winter, Potter arranged for men to build a house on the line between the two quarters. In the spring of 1886, Lulu Potter, an adopted daughter and Lulu’s brother traveled by train from Iowa to Ipswich, where they met Potter. Potter listed the items he took with him in order to farm as four medium-sized mares and harness, three cows, two dogs, two wagons, one mower, hay rake, hay rack and household goods that included a new organ.

“John Sawinsky met me in Ipswich with a team and a wagon. We hauled everything out in three loads including some coal and lumber enough to build a barn. I found the house all ready,” Potter wrote.

Potter did not describe the house he had built on the claim. With little or no timber to construct a house or outbuildings, prairie homesteaders often built houses out of sod. They cut sod into strips and stacked them to build walls. Settlers secured poles to form rafters over which they laid boards, prairie grass and sod. People can see sod houses at the Museum of the South Dakota State Historical Society at the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre, and at Badlands National Park. Other homesteaders built board claim shanties.

“The following summer was the driest we ever had. I sowed about 25 bushels of wheat and threshed 120 bushels. That was better than lots of them did,” Potter wrote.

He built a sod barn, making 27 trips to the river for wood and poles to cover the barn. Potter described the winter of 1886-87 as severe.

“I promised my Maker many things, that if he would take care of us until spring, I would get out. Feed got so scarce that a man offered me eleven good cows for my organ that I paid $75 for. I dared not trade, as I had all I could do to get what stock I had through the winter. Lots of stock perished along the river. They had plenty of hay but it was drifted under and they could not get to it. But spring came and the snow commenced to melt and as the snow melted, our feeling for South Dakota softened too and we stayed.”

In 1887, Potter had a well put down, fenced a pasture and raised 700 bushels of wheat. The year 1889 was a good year for crops, he wrote, and he raised 1,100 bushels of wheat and received $1.11 a bushel. Crops were fair two years later, “but no price for anything. Sold a fine pair of 4-year-old steers with yoke on for $45.00; a pair of young horses for $100.00.”

Potter put money into cows and horses, and had about 50 head of cattle and 20 horses when he rented out the farm in the spring of 1895 and moved to Bangor. Potter served two terms as county treasurer, established a business, served as the first mayor of Selby and was appointed justice of peace. He and his wife, who died in 1925, had two sons, Clarence and Claud. At the time of his death on March 6, 1930, Potter still owned the land on which he homesteaded. He was the last Civil War veteran in the county, according to the Selby Record.

“Mr. Potter has ever been one of the county’s most honored and respected citizens and his passing is a heavy loss to a community larger than Selby and vicinity,” stated an article about Potter in the Selby Record. “To undertake to enumerate his lesser services to county, town, and community would be an almost endless task and would make a history of the county. He was ever ready to help with any good cause.”

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.