June 2014 - South Dakota Firsts

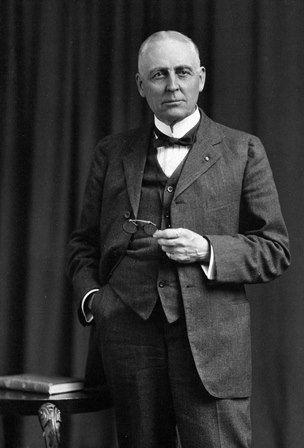

Doane Robinson

South Dakota is celebrating its first 125 years of statehood, as North Dakota and South Dakota entered the union on Nov. 2, 1889.

In “Doane Robinson’s Encyclopedia of South Dakota,” the state historian compiled a list of some of the first things and first incidents in South Dakota history. This record reflects the times in which it was compiled, as Robinson primarily shows white people’s accomplishments. Robinson’s list, with additional information about subjects, includes:

First white men known to have been upon South Dakota soil: Francois and Louis-Joseph Verendrye, Louis la Londe and A. Miotte, 1742. The Verendryes were French-Canadian explorers searching for a water route to China. The lead plate they buried on March 30, 1743, on a hill in present-day Fort Pierre lay undisturbed for 170 years. The site where the plate was found is now a National Historic Landmark.

First white woman to come into the region: Pelagie LaBarge, wife of steamboat captain Joseph LaBarge. Captain LaBarge entered the service of the American Fur Company upon the Upper Missouri River when he was 17 years old, in approximately 1832. Pelagie came up the Missouri River with her husband upon his steamboat “Martha” in 1847, going to the Yellowstone River.

First homestead to be filed in Dakota Territory: right after midnight on Jan. 1, 1863, at Vermillion by Mahlon Gore. Gore was a Vermillion printer who filed on land in Union County by the Big Sioux River. Landing a job with the Sioux City Journal in 1864, he hired a family to care for his claim. They contested the claim and won it.

First recorded Christian prayer in South Dakota: by Jedediah S. Smith, near Mobridge, on June 2, 1823. Smith signed on with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1822. The Arikara attacked the party of fur trappers. The survivors dragged the dead and dying men onto the deck of the keelboat Yellow Stone Packet on the Missouri River. Smith volunteered to go for help. Before leaving on this mission, he delivered what his companions called “a powerful prayer.” A mural by Charles Holloway in the house chamber of South Dakota’s Capitol depicts this first recorded act of Christian worship.

First permanent white settlement: Fort Pierre, in 1817, by Joseph La Framboise. La Framboise built a fur-trading post on the west bank of the Missouri River, north of the mouth of the Bad River. This driftwood shack would give Fort Pierre the distinction of being the oldest continuous settlement in South Dakota.

First steamboat to reach Fort Pierre: the Yellow Stone in 1831. Steamboats would revolutionize Missouri River commerce. When the Yellow Stone returned to Fort Pierre in 1832, it carried American Fur Company agent Pierre Chouteau, Jr. The company had moved the fur trading post to a location about three miles north of the mouth of the Bad River and christened it Fort Pierre Chouteau. The name was shortened to Fort Pierre.

First white woman in the Black Hills: Mrs. Annie E. Tallent in December 1874. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had closed the Black Hills to white exploration and settlement. Tallent, her husband and son were part of a group who came prospecting for gold. Her arrival symbolized that white men weren’t only interested in the gold fields of the Black Hills -- they were looking for a home. Tallent wrote one of the first books on the settlement of the Black Hills and was superintendent of schools in the Deadwood area. Tallent is also a controversial figure because of her role in breaking the Fort Laramie Treaty and settling the Black Hills. In an introduction to Tallent’s book “Black Hills, or Last Hunting Ground of the Dakotahs,” reprinted in 1974, South Dakota author Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve wrote: “Annie Tallent’s malicious, bigoted treatment of the Dakota or Sioux Indians would best serve mankind if it were burned rather than reprinted in this edition to perpetuate a distorted, untrue portrait of the American Indians.”

Doane Robinson, who compiled the list of firsts, was himself a man of many firsts. He served as South Dakota’s first state historian, from 1901 to 1926 and again from 1945-1946. It was Robinson’s idea that notable figures be carved in granite in the Black Hills, and he was the first to invite sculptor Gutzon Borglum to the Black Hills to carve what became Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Robinson’s son Will G. Robinson, served as director of the South Dakota State Historical Society from 1946-1968. The Robinson family tradition of preserving the history of South Dakota continues as Doane Robinson’s great-granddaughter, Vicki McLain of Rapid City, serves on the board of directors of the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation. The foundation is the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society.

North Dakota is usually considered the 39th state and South Dakota the 40th. At the moment of signing on Nov. 2, 1889, the secretary to President Benjamin Harrison handed both declarations to the president. The president took the declarations, had the secretary stand on the far side of the desk, shuffle the pages and then signed the declarations. The president also covered each paper so no one could see which page was signed first. After signing, he took the pages, hid them under his desk, shuffled them again, and then handed them to the secretary. No one knows which state was signed into statehood first. North Dakota is considered 39th and South Dakota 40th for alphabetical reasons.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.