January 2016 - The Legendary Hugh Glass and Jim Bridger

His eyes rolled wildly in his head. His teeth chattered. He broke out in a clammy sweat.

Hugh Glass, the man he had left for dead, was standing before him. Was Glass going to end his life? No.

Jim Bridger’s life was spared.

So goes P. St. George Cook’s version of the legend surrounding Glass. The film “The Revenant” starring Leonardo DiCaprio has rekindled interest in Glass’ crawl through northwestern South Dakota and into history.

In August 1823, Glass and Bridger were among a small group of trappers heading west overland to the Yellowstone River by way of the Grand River in present-day South Dakota.

About 12-miles south of present-day Lemmon, Glass was severely mauled by a grizzly bear. Glass survived and began crawling toward the nearest settlement, Fort Kiowa, nearly 200 miles away.

According to legend, Bridger and John Fitzgerald were to stay with Glass until he died, but they abandoned him. When Glass regained consciousness he found himself alone on the prairie without a gun or other equipment. He vowed revenge against the men who had left him for dead.

Glass is said to have found Bridger and forgiven him.

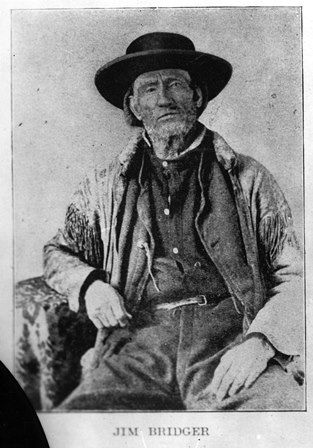

In sparing Bridger, Glass spared the life of a man who would become one of the most important fur trappers and guides in the American West.

The Rev. Pierre Jean De Smet, the Belgian-born Jesuit missionary after whom the South Dakota town is named, described Bridger as “one of the truest specimens of a real trapper and Rocky mountain man.”

De Smet and Bridger first met in 1838, and became lifelong friends, according to Charles Edmund DeLand in Volume XI of “South Dakota Historical Collections,” compiled by the South Dakota State Historical Society.

Bridger came to the Upper Great Plains in 1822 when he answered an advertisement in the Missouri Republican seeking 100 enterprising young men to travel the Missouri River to its source. Bridger worked for various fur trading companies for the next 20 years, roaming the western third of the United States. He is credited with being the first non-Indian to report reaching the Great Salt Lake.

“There was scarcely an accessible spot in the mountains that he was not acquainted with,” wrote DeLand. “He had become a daring leader before 1830 and in that year was one of the partners of the newly organized firm of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. He led his expeditions in every direction, saw many a fight with the Indians.”

With Louis Vasquez, Bridger established Fort Bridger in southwest Wyoming in 1843. The fort became one of the main trading posts for those headed west on the California and Oregon trails.

Bridger was also in constant demand as a guide to military expeditions.

One military expedition would take Bridger back through South Dakota, as he guided for Capt. William Raynolds in an exploration of the headwaters of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. The expedition left St. Louis on May 28, 1859, and traveled on the Missouri River until disembarking at Fort Pierre to travel overland.

Bridger proved to be overcautious and inaccurate as a guide until he reached familiar country in the Yellowstone River region, according to an article in Volume 5 of “South Dakota History.”

Bridger claimed in an article in the Cheyenne Daily Leader that he discovered gold in the Black Hills while with the Raynolds expedition, but according to the “South Dakota History” article, Bridger’s claims had to be measured against the fact that the interview took place after the 1874 Custer Expedition’s report of gold received national publicity.

In 1868, Bridger retired to his farm in Missouri, where he died on July 17, 1881.

In “Mountain Men and the Fur Trade,” Aubrey L. Haines states that Glass never named the men left to care for him after the grizzly’s attack. Fellow trapper James Stevenson wrote that Bridger told him the story of Glass being mauled by a grizzly, but Bridger never said he deserted Glass.

After his encounter with the grizzly, Glass survived several more brushes with death. His luck ran out during the winter of 1832-1833, when he and two companions were killed by Indians as they crossed the Yellowstone River.

A new biography about Glass, “Hugh Glass: Grizzly Survivor,” by historian James D. McLaird will be released by the South Dakota Historical Society Press this spring.

This moment in South Dakota history is provided by the South Dakota Historical Society Foundation, the nonprofit fundraising partner of the South Dakota State Historical Society at the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre. Find us on the web at www.sdhsf.org. Contact us at info@sdhsf.org to submit a story idea.