January 2015 - A Ride Through History

The tall prairie grass would have rolled like waves sweeping across a windy bay.

Stan Johnson imagined how the wind would have swept the prairie grass 100 years earlier as he traveled near Milbank on a passenger train.

In 1941, Johnson’s parents allowed him to travel alone from Chicago, Ill., to Tacoma, Wash., on the Olympian, one of America’s greatest luxury trains of pre-World War II days. Johnson’s stepfather was a conductor on the Olympian and, although he was only 13, Johnson had already made many trips by train from the West Coast to Chicago. Johnson described the journey in “The Milwaukee Road Olympian: A Ride to Remember,” published by the Museum of North Idaho.

The Olympian was operated by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (the Milwaukee Road) between Chicago and the Pacific Northwest. It featured elegant air-conditioned cars, comfortable berths and gourmet dining. The Olympian entered South Dakota near Big Stone City about 5 hours after pulling out of the St. Paul Union Station at 8:40 a.m. Central Time, according to one of the book’s reproduced timetables.

The many Irish and Dutch families who settled near Milbank raised grain and built windmills that ground grain into flour. By the time Johnson traveled through Milbank, the sole windmill stood in the center of town as a historical monument.

The Olympian traveled past Webster, Bristol, Andover, Groton and Bath, all known as ’10-mile towns’ because of the spacing between sidings, Johnson wrote.

Johnson realized the area through which the train was passing had once been prime buffalo hunting country. Now Johnson saw migratory birds, and hoped in vain to see coyotes and pheasants.

The Olympian pulled into Aberdeen’s brick depot on time at 3:50 p.m. and stopped for 10 minutes as train and engine crews were changed.

“The place was planned as a railroad town and had fulfilled expectations,” Johnson wrote. “There was a train in or out of the city every 18 minutes in 1920. West of town were Milwaukee-run stockyards for cattle, sheep and hogs, and in town there was a large freight yard and engine terminal facilities, including a roundhouse.”

Four railroads went through Aberdeen in 1941, and branch lines radiated from the city.

At Ipswich, a town that had once led the nation in the shipping of bison bones that were used for fertilizer, the grade began to climb. A small geological marker near Selby noted the edge of the Great American Desert and the beginning of the true West. Johnson’s plans for this trip’s introduction to the West began in Mobridge.

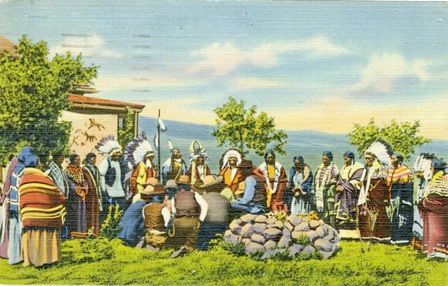

During summers in the 1930s and 1940s, Lakota dancers met the Olympian when it made a 12-minute stop at Mobridge. It became an event eagerly anticipated by train passengers.

“The Indians dressed in the most gorgeous of ceremonial outfits: full eagle-feathered headdresses, buckskin fringed leggings and skirts with beadwork, small bells and porcupine quills sewn in intricate designs, and exquisite handmade moccasins with still more beadwork on their feet,” Johnson wrote.

The group would dance several short dances to the beat of a small drum that one of the children would play.

“It was exciting to be there close to them and to witness something unquestionably genuine and real. It was like someone operating a window back into history,” Johnson stated.

After leaving the depot at Mobridge, Johnson looked down into the yellow-brown water of the Missouri River as Olympian crossed the Missouri River bridge. The first train steamed across the bridge in March 1908.

“The trusses of the bridge, angled for strength, slipped past the window on an oblique pathway that caused them to appear to be moving first up and then down, almost as though they were involved in some sort of rhythmic dance. The bridge was long, nearly as long as 10 football fields laid end to end, so there was plenty of time to enjoy the experience,” Johnson wrote.

Johnson realized that the Missouri River divided the state into two different areas: the prairie grassland of the west side and the crop farming of the east side. He also noted that South Dakota landscape could be characterized as being one of two types. “Either it is gently rolling grassy plains with low rounded hills, or a harsher, sterner countryside of hills and gullies eroded by the sun and wind and water, watched over by higher and sharper hills.”

The Olympian reached Lemmon at 7:30 p.m. Mountain Time.

“The town and countryside looked like a movie Western gunfight set, but historically Lemmon had been known as one of the places where ranchers raising sheep and cattle and those farming got along especially well,” Johnson wrote.

The Olympian soon entered North Dakota, and Johnson continued on his memorable ride to Tacoma. Johnson became, among other things, an elevator operator, a newspaper reporter and an academic psychologist. But mostly, he remained a man who knew and loved railroads.