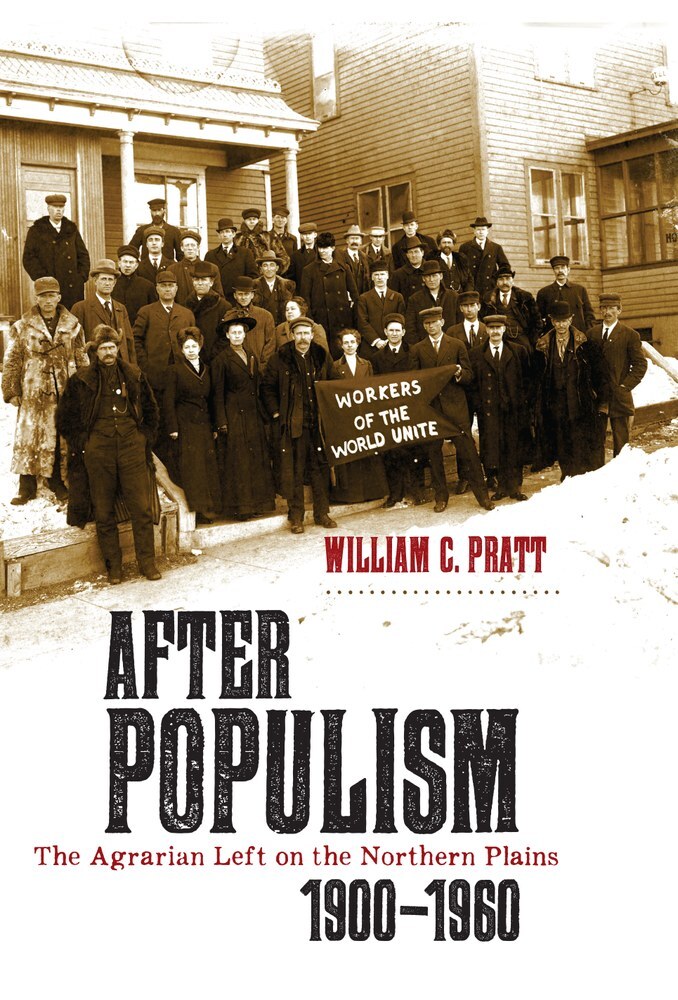

After Populism

Populism, a farmer-led movement that called for sweeping economic reforms, became a major political force in the 1890s. Though short-lived, Populism’s heyday has received ample attention from historians of the Northern Great Plains. But how did agrarian radicals and left-of-center farmers’ groups in the region respond to the massive political changes of the twentieth century? This collection of essays by historian William C. Pratt sheds light on this period by tracking the evolution of rural activism and its impact across space and time.

This broad, analytical history of agrarian movements on the northern plains pays close attention to local particularities and variations from national and even international trends. After Populism explores farmers’ relationships to Socialist groups; the persistence of radicalism in isolated plains communities; agrarian radicals’ involvement in local affairs; women’s roles in radical farm groups; the importance of the Farmers Union in regional and national politics; repeated, unsuccessful attempts at third-party organizing; and the gradual decline of progressive farm protest in the late twentieth century.

Pratt’s work builds on research in collections from throughout the Great Plains, as well as documents from the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History in Moscow and Federal Bureau of Investigation records. In addition, he pulls from decades of personal interviews and site visits, allowing him to add colorful anecdotes that help bring his subjects to life on the page.

After Populism is a must-read for historians of the Northern Great Plains and anyone interested in farm politics. This vital collection of work from a prolific historian of the region brims with unique insight into an important yet understudied topic.

This broad, analytical history of agrarian movements on the northern plains pays close attention to local particularities and variations from national and even international trends. After Populism explores farmers’ relationships to Socialist groups; the persistence of radicalism in isolated plains communities; agrarian radicals’ involvement in local affairs; women’s roles in radical farm groups; the importance of the Farmers Union in regional and national politics; repeated, unsuccessful attempts at third-party organizing; and the gradual decline of progressive farm protest in the late twentieth century.

Pratt’s work builds on research in collections from throughout the Great Plains, as well as documents from the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History in Moscow and Federal Bureau of Investigation records. In addition, he pulls from decades of personal interviews and site visits, allowing him to add colorful anecdotes that help bring his subjects to life on the page.

After Populism is a must-read for historians of the Northern Great Plains and anyone interested in farm politics. This vital collection of work from a prolific historian of the region brims with unique insight into an important yet understudied topic.